Vaudeville

The Big-Time verse The Small-Time

The Keith-Albee and Orpheum Vaudeville circuits were referred to by Variety magazine, the trade journal of the variety industry, as “the big-time.” The performers who worked in these chains of theaters were just as likely to call them the “two-a-days” because there were just two performances given each day, an afternoon matinee and a later evening performance. In the first decade of the 20th century a different type of variety theater began to challenge the two-a-day: the Continuous Vaudeville theater, or as Variety called them, “small-time” Vaudeville.

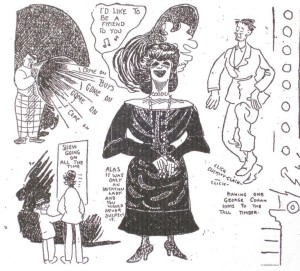

In August of 1907 Chicago Tribune cartoonist Clare Briggs went to the Congress Theater near the corner of State Street and Congress Boulevard to experience a show in one of these nickel theaters. It is a tongue in cheek review requiring more than one grain of salt. Remember, Clare Briggs was also on occasion a performer on the Orpheum Circuit drawing pictures with witty repartee (well witty in Brigg’s opinion). Nevertheless, he seems to have captured some of the ambiance and operation of a small-time continuous Vaudeville theater.

August, 1907

“Evidently Chicago playgoers have not discovered the Congress, where for 5 cents they can get quite as much entertainment (if they have the proper sense of humor) as they can in the higher priced houses. For 5 cents they get the best seat in the house and see a performance which, if given at Lake Forest, would be heralded everywhere.

But the artistic atmosphere which pervades everything connected with the Congress is unique among theaters. The performers beyond doubt are the most nonchalant entertainers in the business, but no more so than the audience. It appears to be against the rules to laugh (except as part of the act), or for any one to move a hand or smile. Possibly every one in the audience is afraid that some one who knows him may see him there, and the performers appear to be suffering from the same complaint.

Possibly one of the biggest hits in the show is the fact that at one side of the stage, against the piano, hangs a big watch, which each performer faces while he works and appears intent on quitting at the exact second. The feature of one of the matinees this week was a backward jump from the stage by one comedian who had overstepped his time two seconds and jumped 6 feet 8 inches backward down a flight of stairs possibly through fear that the walking delegate of his union might upbraid him for working overtime.

It is said that the only disturbance ever created in the theater was by a partly soused member of the middle class who applauded vigorously, not knowing that the rule of the house is that all emotion must be suppressed. He was jumped on by the others in the audience because he might have prolonged the act, and it also is said that the performer helped throw him out for daring to try to make him work overtime.

Persons who attend performances where the hoi poloi manifest enthusiasm, and vulgarly display their emotions, will find relief at the Congress, and learn that audiences at 5 cent theaters do not indulge in such displays nor seek to make the employees work overtime.

That is another unique feature of the Congress. The actors are not artists, but employees. The sign on the stage-door says: “No admittance except to employees.” The walls are done in red calcimine, relieved by signs which read: “Change of program Monday and Thursday.” “Come in any time. Show always going on.” “Performance from 1 to 10:30 p.m.”

The Congress is modest. It does not blare forth in announcements of its attractions and has no press agent to send around word that Miss Orville has lost her diamonds or that Klaw & Erlanger have offered Mr. Beach $40,000 to star in a new comedy next season. But, in spite of this, the Congress gives ten performances per day, seven days a week and plays nearly to capacity each performance, and crowds in a few extra evening performances if necessary.

The stage at the Congress is built for economy of time and trouble, with the laudable intention of doing away with long waits between acts and unnecessary shifting of scenery, so annoying in theaters. There are no walls or delays at the Congress.

One audience passes out while another is entering. There is another virtue. A spectator is privileged to remain as long as he pleases, and for the small sum of a nickel, a half a dime, 5 cents, he can see nine and a half hours of action providing he can stand it. The management last week discovered a spectator they are willing to back in any kind of an endurance contest. He remained in the house from 3 p.m. until the lights went out. The management does not say how long he slept.

As soon as one audience is dismissed the gentlemanly announcer says: “Those who desire may remain and see the next performance, which will start in five minutes.” Such cordiality of welcome and generosity is unknown in first class houses, so-called, but the object of the Congress is philanthropic, and during hard rain storms several persons have been known to remain through two entire performances.

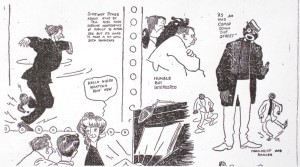

During the five minute intervals between performances the gentlemanly announcer, always willing to oblige, and doing his best both for the public and the house, steps out into the lobby and modestly announces to the throngs passing along State Street the merits of the show. His voice which has timbre which makes one suspect he comes from the Wisconsin woods, competes with the band of the museum up the street, drowns the clatter of passing cars, the howls of the barkers at the Nickelodeons, Therateriums, Museums, etc. across the street and the pleadings of the runners for the second hand stores. His feat in making himself heard is one of the enjoyable things connected with the Congress.

Occasionally passersby stop and drop in, and after five minutes the gentlemanly announcer sticks his head inside the curtains of the lobby and announces: “First on the program will be Mr. Mack.”

He doesn’t say Mack, nor does it sound like Mack. It sounds like an automobile tire exploding. You find out what he said by reading the sign outside after the performance.

At this a tall and passing fair young woman, with her hair arranged after the style affected by farmers in piling hay in the field, comes in through the door for “Employees Only,” chewing gum with great force and expression, and seats herself at the piano, whereupon a nice looking young man chases a small boy out of the front seat near the piano, and begins conversing with the pianist, who strikes up that beautiful classic known as “Turkey in the Straw” in some sections of the country, and “Natchez on the Hill” in others.

“Miss R-R-R-V-ill” as the gentlemanly announcer calls her, with the apparent effort to imitate a building growling, is one of the wonders of the theatrical profession. She is, so far as is known, the only pianist who can chew gum, play the piano, sing an illustrated song, and gossip with her best fellow at the same time-and do them all well.

As the beautiful strains of “Turkey in the straw” fill the auditorium and float out into the lobby and around the corner into Congress Street Mr. Mack appears. He is tall-extremely so-and built on the skeleton construction plan. He comes on with the air affected by clerks in downtown stores who are ten minutes late ringing in, and looks as if he had begged ten minutes off from the necktie counter in the nearby department store to do his set.

The music, however, appears to galvanize him into life. The gentlemanly announcer does not take time to tell what Mr. Mack is going to do, so the audience is left in a state of delightful anticipation. Mr. Mack does an act which appears to be an imitation of clothing store dummy with electric wires crossed inside him. He disdains entirely to permit any expression, no matter how fleeting, to cross his face, and moves with the grace of an automation, keeping both eyes on the clock, and at the psychological second which is the fifty-ninth second in the third minute, he bats both feet hard on the floor and exits just as if he had run down.

Half a minute later the gentlemanly announcer says “B-r-r-r-blut,” which may be either a name or something else and a gorgeous apparition comes through the doorway. The gown is décolleté and is a beautiful creation of 9 cent percale. The stockings are black and of the 8 cent cotton variety. A necklace of beads is worn, a la lariat, around one of the most wonderful décolletages in the world. The first glimpse at the vision recalls the fiery Bucephaluses that used to pull the carettes.

The gentlemanly announcer again leaves the audience in mystery as to what Mlle “B-r-r-r-blut” is going to do, but the pianist gives a clew by reaching for the piano with both hands. The vision on the stage begins as if to do an imitation of a phonograph and starts something that recalls faintly the art of singing. Occasionally a word becomes almost visible in the mass of sounds and at the end of each verse one can distinguish “Won’t you throw a kiss to me?”

Nobody does, neither does anybody throw anything else, which shows that the levee audiences, like society ones, repress all emotion. Getting away with that appears to encourage the vision, and it essays something risque. It even, at two separate and distinct times, kicks up one foot and plays with its beads nervously, while it gets rid of an alleged coon song with a charming refrain which runs “Then you’ll get all that’s coming to you-and a little bit more.”

The audience manifests no emotion, but a large fat man, who has been perspiring freely and almost with audible splashes, arise as if he has had all that is coming to him-and a little bit more-and retires, sprinkling the floor as he goes.

At the conclusion of the charming ditty the employee with the voice that gives the impression that there is a record inside her jerks off a wig and reveals a head of short hair, retiring to leave the audience mildly curious as to whether it was a woman or a man.

“Jubba-ka-blup, blup, blup, by Miss B-v-v-l,” declares the gentlemanly announcer, which, being translated from barker into English by the aid of the signs and tokens, probably meant that Miss Evelyn Orville would sing “Just Because I Loved You So.”

At any rate, the gentlemanly announcer, having sold a few tickets and attracted a few more passersby into the theater, walked over and switched off some of the lights and a moving picture machine flashed on the back of the stage, just as the lady with the hayrick pompadour started in to perform the wonderful feat of singing an illustrated song, chewing gum, playing her own accompaniment, and conversing with her best fellow at once. The feat really was well done, and without the aid of nets or ropes.

Somebody back of the back wall languidly shoved pictures through the machine. It was a beautiful song, all about a sailor lad who loved her too well to stay at home. That seems to be a peculiarity of sailor lads. Anyhow, the scenes showed him bidding her farewell, and she on the cliff, looking across the sea, and the storm, and battle, and the meeting the other girl, and all sorts of heroics and complications.

During this the pianists kept hard at work and the audience didn’t know that she sang some of her conversation with her best fellow instead of the lines of the song. She closed with “Just because I loved you so-” and chopped off the long closing note in the middle, and, without taking a breath, added to her fellow “I told Jan he was a skate-”and at the same time started playing a jig.

The gentlemanly announcer stuck his head in from the box office and remarked: “Br-crum-b-b,” which meant, that it was Bill Crumbly’s turn. Bill is one of the gentleman we went to war over, and the lack of enthusiasm with which he was greeted didn’t stop him. It didn’t even check him.

Bill is one those “Ah started downtown this morning,“ comedians. You know the style, the one who starts downtown and keeps going a little bit further all the time with something supposed to be funny in the conversation line happening every block. You know the style, the kind that gets into the jail, and the workhouse, and hospital and fights his wife, and that sort of thing.

Bill’s progress downtown that morning had been strenuous. As near as can be traced, he started downtown from about Twenty-sixth and State streets, and exchanged repartee with friends at every corner down to State and Madison. Yet no one in the Congress appeared to wish that Bill and taken the elevated and hurried.

At the first corner Bill met a man who inquired what car he took to get to jail. Bill told him he didn’t take a car, he took a pair of pants. The stranger wanted to know how long it took, and Bill informed him it took fifteen minutes to get out and six months to come back.

“Ye-he-he,” Bill just had to laugh at himself. That was the only laugh permitted. No one else cracked a smile, but Bill persisted in “Ye-he-heing” every block.

Then Bill went into a saloon to get a drink and bet the bartender he could swallow the whiskey without a drop touching his throat. He bet 8 cents. The bartender won, but the drink only cost Bill 8 cents. Instead of taking the beer mallet to him, the bartender asked him to have another drink. Bill poured a big one and the bartender said “What do you call that?” “A smile,” replied Bill. “Then for heaven’s sake, don’t laugh or I’ll be ruined,” responded the bartender.

The wit of the bartender made such a hit with Bill that he “Ye-he-heed” once more. He got on the car, evidently along about Fourteenth street, and smoked, and had a perfectly riotous time, taking off his shoes, after which the woman who had objected to his smoking asked him to light up again. “Ye-he-he.”

Bill evidently got off the car at State and Madison and felt so good about it he did a song and dance. Bill can dance some, but he had to sing a song with it. It was a song about trying to borrow 10 cents. His credit evidently isn’t good, for his friend turned him down, whereupon Bill choruses about what he would do “If I ever get $1 again,” and concluded that $1 is your only friend when you’re down and all in. After which Bill, sighting the watch, observed that he had worked four seconds overtime and took a flying backward leap off the stage, ignoring the steps and disappeared.

“B-r-r-I-g-g” growled the gentlemanly announcer, doing his best imitation of an auto stalling in the mud, whereupon Mr. L. E. Beach appeared in what he evidently believed to be a bucolic costume. Mr. Beach belongs in grand opera. Nothing funnier ever was seen outside of Parsifal. He wore his hair done up in a ridge on top and he proceeded to reveal all his domestic affairs, how he met his wife while skating, and when she feel down that broke the ice, and how they had been married thirty years and never had a fight in the house, but always went into the backyard, and his adventures in the hospital, and with his daughter who wore bloomers, etc.

Then, rather unexpectedly, Mr. Beach announced that he was going to sing an operatic selection from “The Bohemian Girl” – which he did, as he said, in “High G on the Haw side,” Mr. Beach has at least one virtue. He sings in English, and the words mean something. He cut out the words used in the opera and sang good old American words with much operatic effort. His chest expansion exceeds Calve’s.

The story of the solo, as transposed into English, was about a country courtship, where he went to call on his girl and she served cider, and the words run something like this:

And mouth to mouth, and jaw to jaw,

We sucked cider through a straw

And mouth to mouth, and jaw to jaw,

We sucked cider through a straw-aw-aw.

And now I have a mother-in-law

From sucking cider through a straw-aw-aw.

And now I have a mother-in-law

From sucking cider through a straw.

At $25 a set to hear De Reszko do it and 5 cents to her Beach, take Beach.

The refined, elegant, and delightful entertainment concluded with a chaste and elegant moving picture depicting the virtues of counterfeiting, and making a heroine of the charming little French girl who deceived the detectives.

It was all instructive and entertaining and well worth the price of admission.”

Yes, apparently many people agreed with Mr. Briggs that Continuous Vaudeville was worth the price of admission which was why so many new nickel theaters were opening up across America and especially in Chicago. the Keith-Albee and Orpheum circuits would continue to grow and yet have their heyday but it was the Continuous Vaudeville companies that eventually grew into entertainment giants that are extant today. Almost coeval with Brigg’s visit to the Congress Theater, Aaron Jones was building his flagship Continuous Vaudeville theater, the Orpheum, a couple of blocks north on State Street. And both William Swanson and Carl Laemmle had already opened nickel theaters that would evolve into Universal Pictures. A nickel theater in Douglas Park would grow into Balaban and Katz and eventually become part of the Paramount Pictures conglomerate. In New York, a chain of nickel theaters grew into MGM, “the studio of the stars.”